|

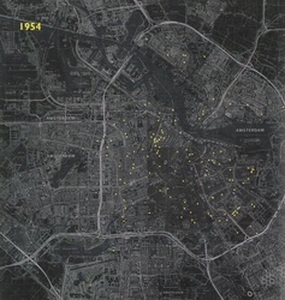

Van Eyck playgrounds identified in yellow within Amsterdam during 1954

Van Eyck playgrounds identified in yellow within Amsterdam during 1961

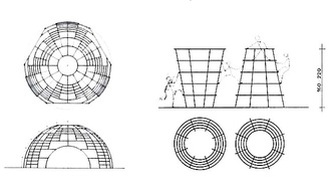

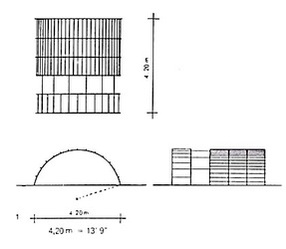

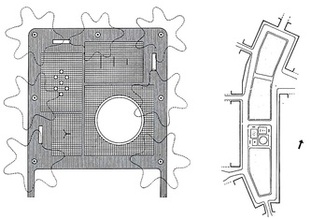

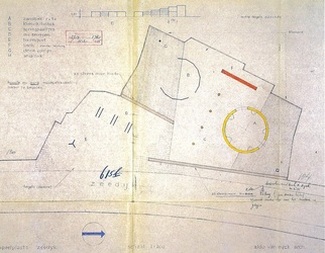

Drawings for climbing igloo (1956) and funnels (1957) Drawings for climbing arch (1949) Plan and situation of Zaanhof playground (1950)

Zeedijk playground, Amsterdam- Centrum (1956)

|

Architecture Case Study by Ki Jun Lo

Amsterdam PlaygroundsAldo van Eyck, Amsterdam Public Works Department, 1947-1978

The street playgrounds in Amsterdam designed by Aldo van Eyck represent one of the most emblematic of architectural interventions in a pivotal time: the shift from the top-down organization of space by modern functionalist architects, towards a bottom- up architecture that literally aimed to give space to the imagination. Recognising the importance of ‘learning’ from the particularities and irregularities of left-over, insterstitial-spaces in the existing fabric of the city, this project aims to work with these spaces rather than overlook them. It is an attempt to express the genius loci of the site through its own unique configuration as all the playgrounds are site-specific, filling them with activity in response to the urban framework as a whole. The project reused vacant plots of land and converted them into playground spaces for children. It was a regeneration of urban voids, filling them with life as a redeeming, therapeutic act of weaving together the fabric of a devastated city. This interstitial approach to the city aims to build a more active community, with at least one small public playground in every neighbourhood of Amsterdam. The playgrounds were an opportunity for van Eyck to test out his ideas on architecture, relativity and imagination, representing his exercises in non-hierarchical composition. Approach The playgrounds posseseses an inherently web-like quality when perceived as a whole, represented through its approach in creating a pattern of relationships with its surrounding: the “in-between” or “interstitial” nature of the playgrounds. The design of the playgrounds is aimed at interaction with the surrounding urban tissue. Temporality of the intervention is part of this ‘in between’ nature, recreating space through incremental adaptation instead of the tabula rasa approach of modernism, where the designs had an autonomy of their own, based on abstract data and statistics. In affiliation with the Site Preparation Service of the Department of City Development who wanted to give every neighbourhood its own playground, they often had to be placed in vacant, derelict sites. The use of empty plots therefore represents a tactical solution in repurposing unused land with an ad hoc approach. In regards to the spatial configuration of the playgrounds, the design proposes a different conception of space, one that stimulates the imagination of the users (the children). Van Eyck consciously designed the equipments in a very minimalist way, the idea being that the children could appropriate the space by it’s openness according to their own interpretation. The close relationship between van Eyck and the artists from the COBRA art movement makes it probable that much of his early inspiration for the playgrounds was derived from COBRA’s working method of spontaneity and experiment. They believed that the spontaneity of the child’s imagination, untainted by modern protocol, was one of the privileged sites of authenticity in a society where man was to live “in a morbid atmosphere of artificiality, lies and barrenness”. It is through these approach in notions that the designs for the playgrounds show great variety and authenticity at the same time through its spatial composition and quality. Scales The playgrounds work across multiple scales from the national scale of Netherlands when perceived as a whole, to small-scaled interventions through the playground furniture van Eyck developed. The playgrounds forms a continuous network of places spread through the urban fabric, furnished with recurrent type-forms designed by van Eyck. These elementary constructions with powerful simplicity in design represents an intent by van Eyck to activate the childrens imagination, rather than shutting it down by adapting the shape of imaginary animals which do not belong in the city. They then offer children the means of discovering things for themselves and develop the locomotion to which they are naturally inclined, hinting towards another possible Program The design of the playgrounds incorporates the activity of the children who use it into the composition of the playground itself. As the program outlines a playground to accommodate children activity, the play equipments is an integral part of the design. Van Eyck himself designed the playground equipment, including the tumbling bars, chutes and hemispheric jungle gyms, and his children tested them, realizing its purpose to stimulate the minds of children. Children could then recognize these spaces instantly as his own territory; places that the child could identify from neighbourhood to neighbourhood as giving due recognition to his existence as a city dweller. That being said, the hemispherical jungle gym is not just something to climb. It also represents a place to talk, as well as a lookout post. Relieved of their childish commotion, the elementary tectonic forms of the playgrounds establish public places with a distinct urban character, places that also make sense to the adult, as a respite when travelling through the city or as a rendezvous. These sandpits, tumbling bars and stepping stones are therefore placed throughout the Netherlands as part of an open space network accessible to the public, regardless of age. How The compositional techniques van Eyck used to articulate the spaces within the design for the playgrounds is achieved through the establishment of a focal point that binds all its elements together. The focus, which is generally marked by the sandpit, rarely if ever coincides with the geometric centre of the site. It produces an asymmetric situation which is then brough into dynamic equilibrium by the positioning of the other elemens. These elements - tumbling bars, stepping stones, chutes and hemispheric jungle gyms - could endlessly be recombined in differing polycentric compositions depending on the requirements of the local environment. This fixed repertiore conveys the modular character of the playground, whilst being uniquely specific to its distinct site. Challenges and Opportunities Like many public infrastructure initiatives the challenge is maintaining these public fixtures to ensure a long-lasting permanence. Unfortunately this unique urban design heritage has been treated in a particularly careless way since the 1970s. Most of the playgrounds were neglected, many were subject vandalism, and demolition. Images All sourced from: Aldo van Eyck: the playgrounds and the city Liane Lefaivre; Rudolf Herman Fuchs; Ingeborg de Roode; Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam. Netherlands, 2002 |